英:schema L; 法:schema L

在1950年代开始出现于拉康著作中的各种“图式”(schemata), 皆是旨在借助图解而对精神分析理论的某些方面加以形式化的企图。这些图式统统是由被若干矢量联系起来的若干位点所组成的。图式中的每一位点都由拉康代数学 (ALGEBRA)中的一个符号所命名,而那些矢量则表示这些符号之间的结构性关系。这些图式可以被看作拉康思想在拓扑学 (TOPOLOGY)领域中的首度入侵。

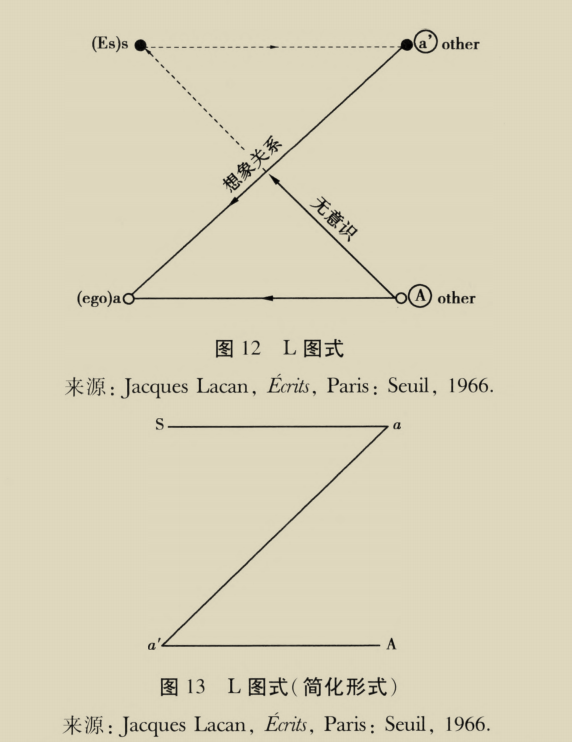

在拉康著作中出现的第一个图式也是他使用最多的图式。这个图式被命名为“L”,因为它很像大写的希腊字母“∧”,即lambda (见:图12,取自Ec, 53)。拉康最初在1955年引入了这一图式 (S2,243), 而在接下来的几年里它也一直在他的著作中占据着一个核心的地位。

两年后,拉康又以一种较新的“简化”形式取代了该图式的这一版本 (图13,取自Ec, 548: 见:E, 193).

尽管L图式允许有很多可能的解读,但是这一图式的主旨还是在于证明(大他者与主体之间的)象征性关系总是会在某种程度上受到 (自我与[[specular image 镜像]]之间的)想象轴所阻碍。因为它不得不穿过想象性的“语言之墙”,所以大他者的话语便会以一种中断且颠倒的形式抵达主体(见:[[Communication 交流]])。因而,这个图式便阐明了在拉康的精神分析概念中如此根本的想象界与象征界之间的对立。这一点在治疗上具有实践的重要性,因为分析家通常都必须在象征辖域中而非在想象界中来进行干预。因而,这个图式也可以说明分析家在治疗中的位置:

如果我们想要把分析家放置进有关主体言语的这一图式当中,那么我们便可以说他处在A处的某个地方。至少,他应当在那里。如果他进入了阻抗的偶联,这恰恰是他被教导不要去做的事情,那么他便会从'处言说,而且他也将在主体身上看到他自己。

(S3,161-2)

通过把不同的元素放置在这一图式中的四个空位 (cmpyloc)上,L图式便可以被用来分析在精神分析治疗中所遇到的各种关系的布景。例如,拉康就用它分析过杜拉与她故事中的其他人物之间的关系 (S4,142-3; 见:Freud, 1905e),也用它分析过同性恋少女个案中的不同人物之间的关系 (S4,124-33; 见:Freud, 1920a).

除了提供一份有关主体间关系的示意图之外,L图式还反映了主体内的结构(就某人可以被区分于小他者而言)。因而,它便以图解阐明了主体的离心,因为主体不应当只是被定位在标记有S的那个位点上,而必须被定位在整个图式之上,“他被延展在这个图式的四个角落之上”(E, 194).

除了L图式以外,还有几个其他的图式也出现在拉康的著作当中(R图式一见:E, 197:I图式一见:E, 212: 两个萨德图式一见:Ec, 774与Ec, 778)。所有这些图式皆是对于L图式的基本四元组的转化,它们皆被建立在L图式的基础之上。然而,不像L图式在1954一1957年一直充当着对于拉康而言的一个持续的参照点,这些图式中的每一个仅仅在拉康的著作中出现过一次。到这些图式中的最后两个(即萨德图式)在1962年出现的时候,这些图式便已然停止了在拉康话语中扮演一个重要的角色,尽管我们可以认为,它们给拉康在1970年代更严格的拓扑学工作奠定了基础。

(schema L) The various 'schemata'that begin to appear in Lacan's work in the 1950s areall attempts to formalise by means of diagrams certain aspects of psychoanalytic theory The schemata all consist of a number of points connected by a number of vectors. Eachpoint in a schema is designated by one of the symbols of Lacanian ALGEBRA, while thevectors show the structural relations between these symbols. The schemata can be seen as Lacan's first incursion into the field of TOPOLOGY.

The first schema to appear in Lacan's work is also the schema which he makes themost use of. This schema is designated 'L'because it resembles the upper-case Greeklambda (see Figure 14, taken from Ec, 53). Lacan first introduces the schema in 1955 (S2,243), and it occupies a central place in his work for the next few years.

Two years later, Lacan replaces this version of the schema with a newer,'simplifiedform' (Figure 15, taken from Ec, 548; see E, 193).

Although schema L allows many possible readings, the main point of the schema is todemonstrate that the symbolic relation (between the Other and the subject) is alwaysblocked to a certain extent by the imaginary axis (between the ego and the SPECULARIMAGE). Because it has to pass through the imaginary 'wall of language', the discourseof the Other reaches the subject in an interrupted and inverted form (seeCOMMUNICATION). The schema thus illustrates the opposition between the imaginaryand the symbolic which is so fundamental to Lacan's conception of psychoanalysis. Thisis of practical importance in the treatment, since the analyst must usually intervene in the

If one wants to position the analyst within this schema of the subject'sspeech, one can say that he is somewhere in A.At least he should be. If heenters into the coupling of the resistance, which is just what he is taughtnot to do, then he speaks from a'and he will see himself in the subject.

(S3,161-2)

By positioning different elements in the four empty loci of the schema, schema L can beused to analyse various sets of relations encountered in psychoanalytic treatment. Forexample Lacan uses it to analyse the relations between Dora and the other people in herstory (S4,142-3; see Freud, 1905e), and also to analyse the relations between the variouspeople in the case of the young homosexual woman (S4,124-33; see Freud, 1920a).

In addition to providing a map of intersubjective relations, schema L also representsintrasubjective structure (insofar as the one can be distinguished from the other). Thus itillustrates the decentering of the subject, since the subject is not to be located only at thepoint marked S, but over the whole schema; he is stretched over the four corners of theschema' (E, 194).

In addition to schema L there are several other schemata that appear in Lacan's work (schema R-see E, 197; schema I-see E, 212; the two schemata of Sade-see Ec, 774and Ec, 778). All of these schemata are transformations of the basic quaternary of schema L, on which they are based. However, unlike schema L, which serves as a constant pointof reference for Lacan in the period 1954-7, each of these schemata only appears once in Lacan's work. By the time the last of these schemata (the schemata of Sade) appear, in1962, the schemata have already ceased to play an important part in Lacan's discourse, although it can be argued that they lay the groundwork for Lacan's more rigoroustopological work in the 1970s.