英:sexual difference

“性别差异”这一措辞虽然在精神分析与女性主义之间的争论中非常突出,却并不属于弗洛伊德或是拉康的理论词汇。弗洛伊德仅仅讲到两性之间的解剖学区分 (distinction)及其精神后果 (Freud, I925d):拉康则讲到性别位置 (position)与性别关系 (relationship),偶尔也讲到两性分化 (differentiation)。然而,弗洛伊德与拉康两人都有处理性别差异的问题,而将这个术语收入词条,既是因为它集合了拉康著作中的一系列重要的相关主题,也是因为它构成了女性主义研究拉康著作之取径的一个重要的焦点 (Brennan, 1989; Gallop, 1982; Grosz. 1990; Mitchell and Rose. 1982).

潜藏在弗洛伊德著作中的基本假设之一,即在于正如男人与女人之间存在某些身体上的差异,所以也同样存在一些精神上的差异。换句话说,存在一些可以被称作“男性”(masculine)的精神特征,以及另一些可以被称作“女性”(feminine)的精神特征。弗洛伊德并未试图对这些术语给出任何正式的定义 (这是一项不可能的任务一Freud, 1920a:SEXVⅢ,171),而是相反限制自己只描述一个人类主体如何渐渐获得这些男性或女性的精神特征。这并非一种本能的或自然的过程,而是解剖学差异与社会性和精神性的因素在其中相互作用的一个复杂的过程。整个过程皆围绕着阉割情结 (CASTRATION COMPLEX)循环往复,其中男孩恐惧他的阴茎被剥夺,而女孩则假定她的阴茎已经被剥夺,从而发展出阴茎嫉羡

遵循弗洛伊德的观点,拉康也着手处理了人类婴儿如何变成一个性化主体的问题。对拉康而言,男性特质 (masculinity)与女性特质 (femininity)并非生物性的本质,而是象征性的位置,而且采取这两种位置的其中一种,对于主体性的建构来说也是根本性的,主体在本质上是一个性化的主体。“男人”与“女人”即代表着这两种主体性位置的能指 (S20,34).

无论在弗洛伊德还是在拉康看来,孩子起初都不知道性别差异,因此也无法采取某种性别位置。只有当孩子在阉割情结中发现性别差异的时候,他才能够开始占据某种性别位置。虽然弗洛伊德与拉康两人皆认为这一占据性别位置的过程与俄狄浦斯情结 (OEDIPUS COMPLEX)有着密切的联系,但是他们在此种联系的确切本质上持有不同的意见。对弗洛伊德而言,主体的性别位置是由主体在俄狄浦斯情结中所认同的父母一方的性别来决定的 (如果主体认同父亲,那么他便会占据一个男性的位置;而认同母亲则需要采纳一个女性的位置)。然而,在拉康看来,俄狄浦斯情结始终涉及对于父亲的象征性认同,因此俄狄浦斯式的认同并不能决定性别位置。因而,根据拉康的观点,决定性别位置的便不是认同,而是主体与阳具 (PHALLUS)的关系。

此种关系要么可能是一种“拥有”(having)的关系,要么可能是一种“没有”(not having)的关系;男人们拥有象征性的阳具,而女人们则没有 (或者,更确切地说,男人们“并非没有拥有它”[sne sont pas sans I'avoir])。采取某种性别位置在根本上是一种象征性的行动,而两性之间的差异也只能在象征性的层面上来设想 (S4,153):

正是就男人与女人的功能是受到象征化的而言,正是就此种功能实际上是被根除于想象界的领域而被定位在象征界的领域而言,任何正常的、完全的性别位置才得以实现。

(S3,177)

然而,根本就没有任何性别差异的能指,其本身可以让主体得以充分地象征化男人与女人的功能,因此便不可能抵达一种充分“正常的、完全的性别位置”。因而,主体的性别同一性 (sexualidentity)便总是一个相当不稳定的事情,也是不断自我质询 (selfquestionning)的一个根源之所在。有关自身性别的询问(“我是一个男人还是一个女人?”)恰恰是界定癔症 (HYSTERIA)的问题。无论是对于男人还是女人而言,神秘的“他者性别/另一性别”(other sex)都总是女人,因此癔症患者的问题(“什么是一个女人?”)对于男性与女性癔症患者来说也都是一样的 (S3,178).

尽管主体的解剖学/生物学 (BIOLOGY)在主体将会采取何种性别位置的问题上扮演着某种角色,然而解剖学并不决定性别位置是精神分析理论中的一项基本的公理。在性别差异的生物学面向(例如在染色体的层面上)与无意识之间存在着一种断裂,前者被联系于性欲的繁殖功能:而在后者中,此种繁殖功能却是不被表征的。鉴于性欲的繁殖功能在无意识中的非表征化 (non-represen-tation),“在精神中便没有任何东西可以使主体借以将自身定位为一个男性或女性的存在”(S11,204)。在象征秩序中不存在任何性别差异的能指。唯一的性别能指便是阳具,而且这个能指也没有任何“女性”的等价物:“严格地讲,就其本身而言,女人的性别是不存在任何象征化的…阳具是一个没有任何对应物,没有任何等价物的象征符。这里的问题在于能指中的某种不对称性。”(S3,176)因此,阳具是“经由阉割情结而在两性身上完成其性别询问的枢轴”(E, 198).

正是能指中这一基本不对称性,导致了俄狄浦斯情结在男人与女人之间的不对称性。男性主体欲望异性的父母而认同同性的父母,女性主体则欲望同性的父母而“需要将异性的形象当作其认同的基础”(S3,176)。“对一个女人而言,她对于自身性别的认识并非在俄狄浦斯情结中通过一种对称于男人的方式而实现,并非通过认同母亲,而是相反通过认同父性的对象,而这便给她指派了一种额外的迂回。”(S3,173)“这一能指的不对称性决定了俄狄浦斯情结所要通过的两条道路,这两条道路都要通过同一条小径一阉割的小径。”(S3,176)

因而,如果就其本身而言根本不存在任何象征符来表示男性一女性的对立,那么唯一理解性别差异的方式便是根据主动性一被动性的对立 (S11,192)。这一两极性是男性一女性的对立得以在精神中得到表征的唯一方式,因为性欲的生物学功能(繁殖)是不被表征的 (S11,204)。这就是为什么一个人要怎样做才显得是一个男人或者一个女人的问题,是一场完全处在大他者领域中的戏剧 (S11,204), 这也就是说,主体只能在象征层面上来实现其自身的性欲 (S3,170).

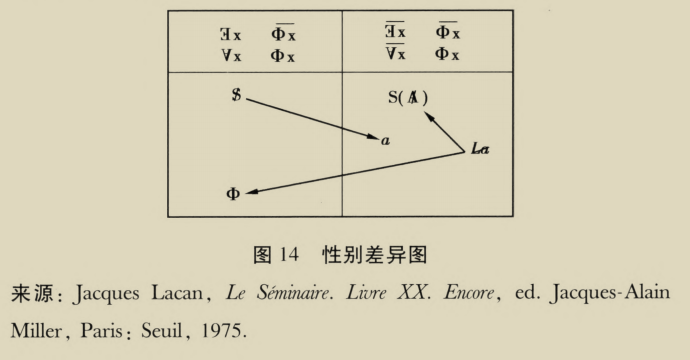

在1970一1971年度的研讨班上,拉康试图借助于一些衍生自符号逻辑的公式来对他的性别差异理论加以形式化。这些公式又再度出现于他在1972一1973年度的研讨班上提出的性别差异图中 (图14,取自S20,73)。这个图分成两边。在左边,是男性的一边;而在右边,则是女性的一边。性化公式出现在这个图的顶端。因而,男性一边的公式是3xx (=至少存在着一个并不服从于阳具功能的x)与Hxx (=对于所有的x来说,阳具功能皆是有效的)。女性一边的公式是3xx (=并不存在一个不服从于阳具功能的x)和廿xx (=并非对于所有的x来说,阳具功能皆是有效的)。最后一则公式阐明了女人 (NOMAN)与“并非全部”(not-all)的逻辑之间的关系。最引人注目的是,在这张图的每一边的两个命题似乎都是相互矛盾的:“每一边皆是由对于阳具功能的肯定与否定,皆是由对于绝对(非阳具性)享乐的包含与排除所定义的。”(Copjec, 1994:27)然而,在两边之间没有任何的对称性(没有性别关系),每一边都反映了性别关系 (SEXUAL RELATIONSHIP)可能失败的一种根本不同的方式(S20,53-4)。

The phrase 'sexual difference', which has come into prominence in the debate betweenpsychoanalysis and feminism, is not part of Freud's or Lacan's theoretical vocabulary. Freud speaks only of the anatomical distinction between the sexes and its psychicalconsequences (Freud, 1925d); Lacan speaks of sexual position and the sexualrelationship, and occasionally of the differentiation of the sexes (S4,153). However, both Freud and Lacan address the question of sexual difference, and an entry has beenincluded for this term because it brings together an important set of related themes in Lacan's work, and because it constitutes an important focus for feminist approaches to Lacan's work (see Brennan, 1989; Gallop, 1982; Grosz, 1990; Mitchell and Rose, 1982).

One of the basic presuppositions underlying Freud's work is that just as there arecertain physical differences between men and women, so also there are psychicaldifferences. In other words, there are certain psychical characteristics that can be calledmasculine'and others that can be called 'feminine'. Rather than trying to give anyformal definition of these terms (an impossible task-Freud, 1920a: SE XVIII, 171), Freud limits himself to describing how a human subject comes to acquire masculine orfeminine psychical characteristics. This is not an instinctual or natural process, but acomplex one in which anatomical differences interact with social and psychical factors. The whole process revolves around the CASTRATION COMPLEX, in which the boyfears being deprived of his penis and the girl, assuming that she has already beendeprived of hers, develops penis envy.

Following Freud, Lacan also engages with the problem of how the human infantbecomes a sexed subject. For Lacan, masculinity and femininity are not biologicalessences but symbolic positions, and the assumption of one of these two positions isfundamental to the construction of subjectivity; the subject is essentially a sexed subject.'Man'and 'woman'are signifiers that stand for these two subjective positions (S20,34).

For both Freud and Lacan, the child is at first ignorant of sexual difference and socannot take up a sexual position. It is only when the child discovers sexual difference inthe castration complex that he can begin to take up a sexual position. Both Freud and Lacan see this process of taking up a sexual position as closely connected with theOEDIPUS COMPLEX, but they differ on the precise nature of the connection. For Freud, the subject's sexual position is determined by the sex of the parent with whom the subjectidentifies in the Oedipus complex (if the subject identifies with the father, he takes up amasculine position; identification with the mother entails the assumption of a feminineposition). For Lacan, however, the Oedipus complex always involves symbolicidentification with the Father, and hence Oedipal identification cannot determine sexualposition. According to Lacan, then, it is not identification but the subject's relationshipwith the PHALLUS which determines sexual position.

This relationship can either be one of 'having'or 'not having'; men have the symbolicphallus, and women don't (or, to be more precise, men are 'not without having it'lils nesont pas sans l'avoir/). The assumption of a sexual position is fundamentally a symbolicact, and the difference between the sexes can only be conceived of on the symbolic plane (S4,153):

It is insofar as the function of man and woman is symbolized, it is insofaras it's literally uprooted from the domain of the imaginary and situated inthe domain of the symbolic, that any normal, completed sexual position isrealized.

(S3,177)

However, there is no signifier of sexual difference as such which would permit thesubject to fully symbolise the function of man and woman, and hence it is impossible toattain a fully 'normal, finished sexual position'. The subject's sexual identity is thusalways a rather precarious matter, a source of perpetual self-questioning. The question ofone's own sex ('Am I a man or a woman?') is the question which defines HYSTERIA. The mysterious 'other sex'is always the woman, for both men and women, and thereforethe question of the hysteric ('What is a woman?') is the same for both male and femalehysterics (S3,178).

Although the anatomy/BIOLOGY of the subject plays a part in the question of whichsexual position the subject will take up, it is a fundamental axiom in psychoanalytictheory that anatomy does not determine sexual position. There is a rupture between thebiological aspect of sexual difference (for example at the level of the chromosomes) which is related to the reproductive function of sexuality, and the unconscious, in whichthis reproductive function is not represented. Given the non-representation of thereproductive function of sexuality in the unconscious,'in the psyche there is nothing bywhich the subject may situate himself as a male or female being' (S11,204). There is nosignifier of sexual difference in the symbolic order. The only sexual signifier is thephallus, and there is no 'female'equivalent of this signifier: 'strictly speaking there is nosymbolization of woman's sex as such... The phallus is a symbol to which there is nocorrespondent, no equivalent. It's a matter of a dissymmetry in the signifier' (S3,176). Hence the phallus is 'the pivot which completes in both sexes the questioning of their sexby the castration complex' (E, 198).

It is this fundamental dissymmetry in the signifier which leads to the dissymmetrybetween the Oedipus complex in men and women. Whereas the male subject desires theparent of the other sex and identifies with the parent of the same sex, the female subjectdesires the parent of the same sex and 'is required to take the image of the other sex asthe basis of its identification' (S3,176). For a woman the realization of her sex is notaccomplished in the Oedipus complex in a way symmetrical to that of the man's, not byidentification with the mother, but on the contrary by identification with the paternalobject, which assigns her an extra detour' (S3,172).'This signifying dissymmetrydetermines the paths down which the Oedipus complex will pass. The two paths makethem both pass down the same trail-the trail of castration' (S3,176).

If, then, there is no symbol for the opposition masculine-feminine as such, the onlyway to understand sexual difference is in terms of the opposition activity-passivity (S11,192). This polarity is the only way in which the opposition male-female is represented inthe psyche, since the biological function of sexuality (reproduction) is not represented (S11,204). This is why the question of what one is to do as a man or a woman is a dramawhich is situated entirely in the field of the Other (S11,204), which is to say that thesubject can only realise his sexuality on the symbolic level (S3,170).

In the seminar of 1970-1 Lacan tries to formalise his theory of sexual difference bymeans of formulae derived from symbolic logic. These reappear in the diagram of sexualdifference which Lacan presents in the 1972-3 seminar (Figure 16, taken from S20,73). The diagram is divided into two sides: on the left, the male side, and on the right, thefemale side. The formulae of sexuation appear at the top of the diagram. Thus theformulae on the male side are (=there is at least one x which is not submitted tothe phallic function) and xx (=for all x, the phallic function is valid). The formulaeon the female side are (=there is not one x which is not submitted to the phallicfunction) and Vxx (=for not all x, the phallic function is valid). The last formulaillustrates the relationship of WOMAN to the logic of the not-all. What is most striking isthat the two propositions on each side of the diagram seem to contradict each other: 'eachside is defined by both an affirmation and a negation of the phallic function, an inclusionand exclusion of absolute (non-phallic) jouissance' (Copjec, 1994:27). However, there isno symmetry between the two sides (no sexual relationship); each side represents a radically different way in which the SEXUAL RELATIONSHIP can misfire(S20,53-4).